I’ve written at length about my childhood aspirations to be an herbalist. These early fantasies dreamed up from the embrace of a favorite apple tree were no doubt romantic and in some ways impractical. But they also held a seed of long-lasting truth that continues to inform how I shape my path as an herbalist and lifelong lover of plants.

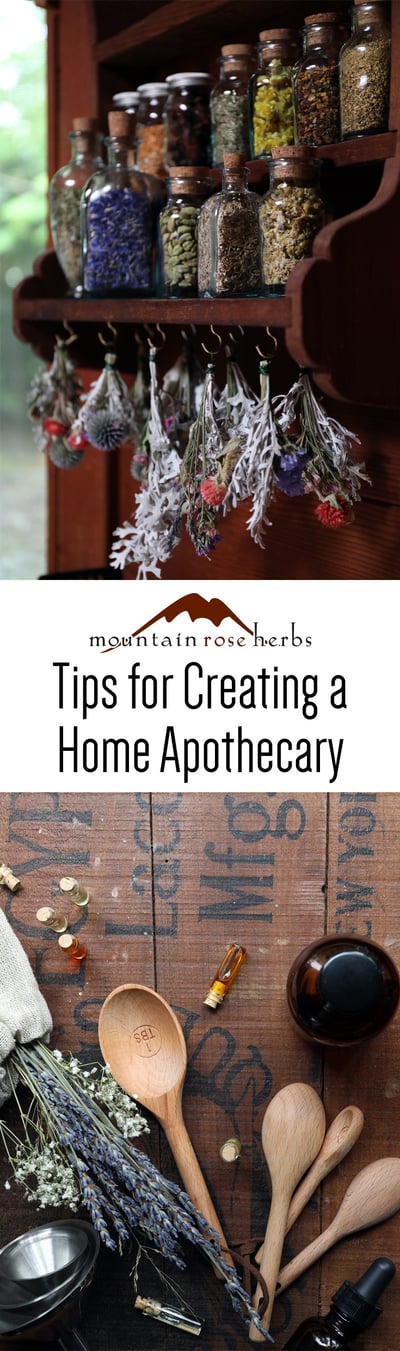

Since earliest memory, I pictured myself in a tumbledown cottage or rustic cabin at the edge of the woods, with a weedy patch of garden interwoven with the surrounding forest, the inside of the cottage strung with bundles of drying plants, and the shelves packed with jars of remedies, mushrooms, and peculiar flowers. Happily, I’ve managed to manifest my childhood dream apothecary in the wild mountains of New Mexico.

The pantry and cabinets in my tiny cottage are packed tight with all manner of wonders—paper bags of carefully dried herbs, antique jars of oil infusing with aromatic plants, blue-tinted bottles of bioregional bitters, stoppered decanters of herbed wines, glass vials of powdered styptics, and sealed canisters of weedy tea blends. There’s a spice chest in the closet, sealed buckets of red root and reishi in the pantry by a bag of rice, decoction pots stacked by the Dutch oven, and every size of funnel hanging next to the spatulas. The liquor shelf is populated not only with my favorite peaty libations of bourbon and scotch, but also with the local spirits and southern specialties I prefer to use in my remedies—smoky mezcal crafted in New Mexico and the apple-scented moonshine of my youth. My kitchen and my apothecary are one and the same. They so clearly reflect the earthy, commonsense approach to herbalism I most enjoy.

The Dressing of the Apothecary

Not everyone’s vision of the ideal apothecary will be the same. There’s a variety of aesthetics, contents, and structure available. Mine is clearly marked by my southern upbringing, my love of the mountains I call home, and my practice’s peculiar blend of the weedy and the otherworldly. But there are as many ways to envision and create an apothecary as there are herbalists. What tends to remain consistent is the high quality of plants, and their clearly prized status.

Organization is also a priority. Every herbalist is likely to know the frustration of searching for the one perfect formula that happens to be in an unmarked mason jar, shoved into some dusty corner for safekeeping. Such events are likely to teach us the value of storage by alphabetical order of botanical names and other such commonsense practices that seem tedious in the beginning but soon become an all-too-obvious necessity.

Whether home, clinical, or retail in nature, our herbal apothecaries exist for the storage, preservation, and distribution of botanically-based remedies. After all, the very word “apothecary” refers to a storehouse, and most any herbalist who has been about this business for any length of time will know just how important (and how challenging) it can be to make room for their ever-expanding herbal abundance. I’m fairly sure I could personally fill a good-sized pantry with just my favorite oils and fats, and that doesn’t take into account the plants themselves!

The real question here is exactly how to structure and organize one’s apothecary.

I’ve seen shiny, perfectly hygienic, clinical pharmacies that bore a great resemblance to mainstream medical facilities—every ingredient sealed and recorded. I’ve witnessed mobile storehouses with all sorts of special accommodations made for traveling with temperature-sensitive plant matter. And I’ve spent time in local trailers and small adobes where the elderly inhabitants keep their myriad remedies wrapped in brown paper and stored in dresser drawers, bedside tables, or occasionally a roomy TV cabinet. In practical terms, it only matters that the apothecary serves to protect the plants and pleases the owner, not that it fit some standardized mold.

The Preservation of Magic: A Brief Ramble on Procuring Herbs & Herbal Preparations

I harvest, preserve, and prepare most of my remedies myself, primarily from locally abundant wildcrafted plants and a few garden “weeds.” However, I’m well aware that not everyone has the time, energy, or means to do so. Even in my own practice, there are some valuable herbs that I can’t procure locally and choose to purchase from farms, fellow foragers, or trustworthy herbal companies like Mountain Rose Herbs.

When I first started out, it seemed truly intimidating to meet anyone of a like mind and overlapping plant passion, since I live many hours from the nearest city. I became a member of a few online forums with a folk herbalism emphasis where I not only made lifelong friends, but also was able to trade and purchase amazing products from folks whose work I knew and trusted. I also decided to host a few small gatherings of my own, just to bring together other folks with a love of wild foods, herbal remedies, and field botany.

Perhaps because of how often I gather my own herbs, I’m especially persnickety about the quality of the plants I purchase. I’m by no means an expert on the subject, since only a small percentage of my remedies are purchased, but I’m picky enough to have a few tips to pass on, especially for those of you without years of hard-won experience.

Whenever I need to source dried or fresh herbs, I think of my search in terms of concentric rings that spiral from the center outward. I prefer to find my herbs close to home, in my own bioregion and from plant people in my local community.

If I have to move up to a larger herbal business, I choose the ones I know have the highest quality and best ethics. In some cases I even prefer certain large businesses with whom I have a long-term relationship, over smaller businesses with more questionable farming or gathering methods.

There’s nothing so disappointing as ordering an important plant or preparation and receiving something ineffective, sub-par, or downright unacceptable. I’ve gotten shiny, foil-wrapped bags of what was supposedly yarrow, but more closely resembled a bundle of scentless hay. I’ve also eagerly cracked open a brand new bottle of supposedly fresh kava tincture, only to be met with inert, flat-tasting alcohol—no tingling of the tongue, no rooty aromatics, no sense of relaxation. These unfortunate experiences turned out to be good learning tools, causing me to more carefully track down the kind of plant remedies I value and need for myself, my family, and my clients.

When I purchase herbs, I want the company to be intimately familiar with every step of its production process. Sometimes, especially at a larger farm or company, this isn’t all one person. But as a whole, the company should be able to talk about the intimate details of their herbs, from exactly where and how they’re grown, to exactly how they’re processed in order to be dried, packaged, shipped, and so on. The best companies, even large ones, are happy to answer detailed questions from their customers regarding even seemingly trivial minutia.

Purchasing Dried Herbs

The best way to assess dried plant material is to be familiar with the living plant. Barring that, I recommend reading descriptions of the scent of the plant and being familiar, if only through photos, with its appearance. This will help you know you’re using the correct plant and also see how close or how far removed the dried material is from its original state.

Some herbs have specific aromatics. Certain plants, like lemon balm, have delicate volatile oils that are easily lost during the harvesting, drying, and storing process. I rarely expect to purchase dried lemon balm and have it be anything close to the fresh plant. However, other plants are tougher and their aromatics can survive great duress. You could toss a bag of dried chamomile on the side of the road in the middle of summer and come back a month later to find it still smelling distinctly of chamomile. Other plants aren’t particularly aromatic, but they should still smell fresh and green, never musty.

For example, elder flowers, tiny as they may be, still retain many characteristics when dried properly. Expect them to be a soft ivory in color, be of recognizable form, and have the peculiar delicate scent for which they’re known. Rosehips should still be a deep orange-red and retain their aromatic tartness if harvested at the correct time and preserved properly. Even delicate plants like Scutellaria have the capacity to retain their properties when dried if handled carefully. So much depends on how much moisture and light the plants have been exposed to.

Roots and seeds can be more difficult to sort out and may require that you break, scratch, or possibly heat them in order to access their aromatics. Dried plants come in a variety of colors and textures. They all change to some degree when dried, but they should generally still be vivid in color and recognizable when compared to the living plant.

Common Sense & Snake Oil: Procuring Herbal Products

With bulk herbs you can generally see and smell the quality, or lack thereof. With herbal preparations, though, it can initially be more challenging. For the most part, it helps if you know the product well before you buy, including having experienced its effects. This makes things especially difficult for beginners, many of whom have read about what an herb is like and what its actions may be, but have yet to experience it for themselves.

Making remedies is precise work. Even those employing the folkloric method (as opposed to abiding by strict measurements and proportions) must deal with detailed tasks that require both sensory and intellectual attention.

As someone who already makes herbal preparations for family and clients, I know that the effort involved in a commercial-scale herbal products company is huge. There’s been a surge in the number of herbal businesses and the size of the herbal community in recent years. This has the great benefit of providing so many more great herbalists’ work to choose from, and it also has the downside of overwhelming selection. With this surge has also come the rise of the essential oil multi-level marketing companies and any number of corporate supplement manufacturers selling low-quality, poorly researched products to folks who don’t know any better. Some examples of this are fairly harmless to humans, but a problem for the plants, as with the strange trend to put rock star herbs like chaga and ginseng in everything, from hair products, to energy drinks, to shampoo.

Not all preparations are created equal, but if you know the plants you’re dealing with, many remedies can be fairly easy to sort out by organoleptic methods. By this, I simply mean understanding quality by using your senses. A high-quality tincture or elixir made with fresh stinging nettles should taste, quite distinctly, of nettle—not just boozy or like musty water. You can also tell when many products are no longer good by their scent, appearance, and other sensory keys. Plantain salve or comfrey oil shouldn’t smell cheesy, but it often does because of the plant’s water content and the tendency for some to either not wilt the plant before infusing, or to not use a double boiler to make sure the moisture is sufficiently removed from the fat.

Familiarity is Key

Familiarity with plants is the key to creating a powerful apothecary. We’re not just collectors of beautiful specimens or archivists of impersonal patent remedies, but characters in the ancient story of people and plants. For longer than we have been human or had language, we have been intimate with the ways of the green world, and we have experienced its effect on body and mind. From spit poultice to ceremonial smoke, these creatures are our elders and our initiators into a deeper relationship with the living earth.

Our apothecaries are not only mason jars of precisely extracted phytochemicals, but a profound connection to the plants themselves. And to each other.

This piece was excerpted from the original guide created by Plant Healer Magazine.

Want More Articles Like This?

You may also be interested in: